What is a walled garden?

A walled garden is a digital environment managed by a single tech company, such as Apple or Meta. Within this closed space, the company controls what users can access, how data is shared, and which apps or services can operate inside it. This allows the company to maintain tight oversight over content, user experience, and monetization, often at the expense of openness and interoperability.

How walled gardens work

The idea behind closed ecosystems is design control. By managing every layer (from software and data to identity systems) within one framework, a company can decide how each part interacts with others.

Controlled access and platform lock-in

Control in a closed ecosystem starts with access. The company decides which third-party apps, features, or integrations are permitted, which payment methods are accepted, and what users can access within the platform.

Over time, these limits can turn into dependence. A user who stores files, pays for content, or builds an audience inside one platform finds the same things hard to move elsewhere. Formats and devices may be incompatible, and accounts may not transfer.

For businesses, reaching the platform’s audience means following its technical rules and commercial terms. Once those dependencies become central to revenue or visibility, leaving the platform is no longer simple.

User data containment

Data is the core resource that keeps a closed ecosystem running. Actions inside it, such as searches, messages, and purchases, generate data that the company processes and stores on its own servers.

Access to user information is governed by the company’s policies. Outside developers and/or advertisers interact with it only through approved channels, usually narrow interfaces that limit what can be seen or extracted. The specifics differ between platforms, but in most cases, detailed user data remains inside the company’s systems.

Most ranking, targeting, and pricing decisions happen within internal code that isn’t open to the public. Outsiders can see what appears on the screen but not how those results are produced. Oversight depends on what the company chooses to disclose and on the requirements set by law or regulation.

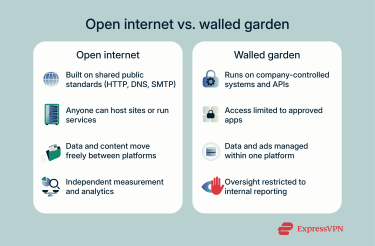

Walled garden vs. the open internet

Unlike a walled garden, the open internet is built on public technical standards that anyone can implement.

Key differences between open and closed platforms

On the open internet, independent services communicate through public protocols. These include HTTP and HTTPS for web pages, Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) for email, and the Domain Name System (DNS) for resolving site addresses. Because these standards are open, anyone can host a website, run a mail server, or create a browser that connects to them. Everything links across providers, and no single gatekeeper decides who gets to participate.

Closed platforms work differently. When outside tools need to connect, they do it through interfaces known as APIs, entry points defined and maintained by the platform. The company can change or remove those connections at will, deciding which integrations stay and which are cut off.

Moving data is another dividing line. On the open web, exports often work through common formats or documented tools that make information portable. Within a closed platform, purchases and stored data remain tied to one account, and even when export options exist, they usually operate under limits the company sets itself.

Transparency and interoperability

On the open web, transparency applies to the technical standards that define how systems communicate. These standards are public, letting developers observe how data moves across the network and confirm that implementations follow the published specifications. Because the rules are openly available, researchers and independent groups can study web behavior and verify technical compliance without relying solely on company statements.

Closed ecosystems are different in that their technical structure and data flow are private, being built around proprietary systems that aren’t usually open to inspection. Companies keep those details to themselves, usually for security or competitive reasons. What outsiders learn depends on what the company chooses to disclose. The lack of visibility also limits interoperability.

Email shows what openness looks like in practice. Messages move between providers because every service uses the same shared standard. In closed systems, that only happens when the company itself provides or approves the link. Anything unapproved simply stays out.

Monetization

On the open internet, revenue is distributed. Publishers sell ads, subscriptions, or goods directly. Measurement relies on browser features and identifiers such as cookies (small files a site asks a browser to store so the site can recognize the same browser later).

Closed platforms usually keep monetization inside the platform boundary. Advertising, payments, and reporting run through the company’s own tools. Because users are signed in, the platform primarily uses first-party data (information it collects directly through its services) to target and measure ads.

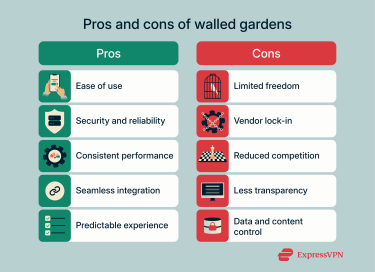

Advantages and disadvantages of walled gardens

Walled gardens persist because they solve real problems. They make digital ecosystems stable and easy to use. Yet the same features that create order also limit freedom and transparency.

Benefits of walled gardens

By centralizing control over software, content, and services, these ecosystems create a predictable environment that particularly appeals to casual users.

Ease of use and convenience

One of the main reasons users stay within a walled garden is simplicity. Walled gardens are designed to keep users within one ecosystem by making their products and services tightly interconnected. For the user, this creates a seamless experience, from setting up a new device to syncing data across services. There’s no need to manually configure settings, install drivers, or troubleshoot compatibility issues. For many people, this “plug-and-play” convenience is worth giving up some flexibility.

Security and reliability

Because walled gardens restrict what can enter the ecosystem, they are often perceived to offer stronger protection against malware, scams, and low-quality apps. Platforms like Apple’s App Store conduct security checks and remove malicious software before it reaches users. This controlled environment creates a sense of trust and reliability. However, this doesn’t mean all fake apps are blocked during these checks: users still need to stay vigilant.

Consistent performance and design

Uniform design standards and hardware–software coordination mean users enjoy smoother performance and fewer glitches. Apps and interfaces follow the same design language, which makes navigation intuitive and reduces the learning curve when switching between devices or apps within the same ecosystem.

Limitations for users and businesses

The same approach that creates a seamless user experience can also be restrictive.

Limited freedom and flexibility

In a walled garden, users are often locked into using only the platform’s approved apps, devices, or services. This makes it difficult and, in many cases, risky to install third-party software, change default settings, or customize the system’s appearance and functionality. As a result, users trade personal control for convenience.

Vendor lock-in

Once users invest time, money, and data into a particular ecosystem, switching to another platform can be costly or inconvenient. Devices, files, and subscriptions are often designed to work best (or only) within the same environment. This lock-in effect can discourage competition and make users dependent on one company’s products and decisions.

Reduced market competition

Because the platform provider controls the ecosystem, prices are less likely to be driven down by competition. Users may end up paying more for hardware, subscriptions, or app purchases than they would in a more open market. Accessories and repairs can also be more expensive when only official options are supported.

Less transparency and choice

Walled gardens filter what users can access, curating search results, app availability, and content visibility. While this can improve quality, it also limits exposure to alternative viewpoints, apps, or services. Users may not realize how much their digital experience is being shaped or restricted by the platform’s rules and algorithms.

Real-world walled garden examples

Some of the biggest tech companies run their products as a proprietary ecosystem, where hardware, software, and services are designed to work exclusively together. From the outside, these systems feel part of the wider internet, but most of what happens inside stays on company infrastructure.

Examples of walled gardens include:

- Apple: Apple’s devices, apps, and services are tightly integrated, creating a seamless experience for users. iPhones, iPads, Macs, and Apple Watches all sync effortlessly through iCloud. Every public iOS app passes through Apple’s store. The review process checks security and technical standards before anything reaches users. Payments made inside most apps are processed through Apple’s in-app purchase system, which manages billing, taxes, and transaction data within Apple’s own infrastructure. For developers, this means steady distribution but little control, prompting some to challenge Apple in court over these restrictions.

- Meta: Meta offers Accounts Center, a system that lets users link their Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp identities for cross-app features like login and changing account settings. External developers and researchers can interact with Meta’s platforms only through approved interfaces, including its business, marketing, and research APIs.

- Google: Google Search still connects users to the wider web, yet many of its features now keep interaction within Google’s own services. Instant answers, product listings, Maps results, and YouTube previews often resolve user queries before they reach external sites. This improves speed and convenience, but it's also concentrating visibility and ad placement inside Google’s network. The model is technically open because the indexed web is still accessible and Google doesn’t block external linking, but nonetheless, much of the engagement stays within Google’s environment.

How walled gardens affect digital advertising

Walled gardens dominate digital advertising because they control both the audiences and the data that power campaigns. Instead of relying on browser-based tracking, advertisers target users within the platform’s own systems, where most user activity is already tied to an account.

Shift to first-party data strategies

As privacy laws expand and browsers restrict third-party cookies, large platforms have shifted toward first-party data as the foundation of their advertising systems.

They now combine that data with contextual signals such as page content, search queries, and device information. Consent, data processing, and reporting all take place within each platform’s controlled environment. The result is a model that gives advertisers access to large, authenticated audiences but keeps most of the data flow internal to each ecosystem.

Decline of third-party tracking

For years, open web advertising depended on cross-site trackers to monitor user behavior and measure conversions. As major browsers and privacy laws restrict these tools, open ad exchanges have lost much of their ability to link impressions and outcomes reliably across multiple websites.

Walled gardens are less affected by these constraints because tracking occurs within their own logged-in environments. Advertisers still get detailed targeting and attribution within each ecosystem. This shift has redirected much of the global ad spend from open networks toward closed platforms, deepening their market dominance.

Budget fragmentation and targeting challenges

For advertisers, the consolidation of data into separate ecosystems introduces complexity. Each platform runs its own ad tools, creative formats, and performance metrics. Campaigns can’t be compared easily across systems, and overlapping audiences lead to duplicated spending.

Smaller businesses face the steepest barrier. Open web advertising once allowed them to reach audiences through shared exchanges with standardized bidding and analytics. Now they must learn multiple proprietary dashboards (one for each major platform) to achieve the same reach.

What this means for users

In traditional open-web advertising, third-party trackers follow users across multiple sites, building massive cross-site profiles without explicit consent. In contrast, walled gardens keep tracking within their own platforms, so advertisers don’t need to rely on external cookies or cross-site scripts. As a result, users experience less tracking by unknown third parties.

But this reduction in cross-site tracking doesn’t mean an increase in privacy: your behavior is still tracked in detail inside the platform. Everything you do while logged in (searches, purchases, app interactions, location, even offline data in some cases) feeds directly into the platform’s profile of you. Platforms combine first-party data with contextual signals and internal analytics to create extremely detailed, persistent profiles.

The result is that users’ activity is more transparent to the platform than it ever was to external trackers. The “hidden third parties” problem is replaced by a single giant entity holding a person’s full profile.

Can a VPN help you protect your privacy inside a walled garden?

Inside a walled garden, a virtual private network (VPN) can have limited effects. These platforms track users primarily through first-party data, meaning everything you do while logged in is linked directly to your account. A VPN can’t stop this type of internal tracking, because the platform doesn’t rely on your IP address or external cookies to understand your behavior.

True privacy within these ecosystems requires a broader approach. Awareness of how your data is collected, careful account hygiene, and permission management can make a meaningful difference. Limiting shared information, disabling unnecessary location tracking, and using separate accounts or browsers for sensitive activities help reduce the amount of data tied to your main profile. Opting out of ad personalization and adjusting privacy settings wherever possible also adds a layer of control.

Using a VPN is still a great way to increase your privacy outside the walled garden. By masking your IP address and encrypting your internet traffic, it protects you from external observers such as internet service providers (ISPs), public Wi-Fi networks, and third-party trackers on the open web. This means that while the platform itself still sees your activity, outside parties cannot easily monitor your behavior or link it to your physical location.

Browsers and services that prioritize privacy

A few widely used tools make it easier to reduce tracking without leaving the open web. They don’t remove all data collection, but they give users more control over what gets shared and with whom.

- Firefox, Brave, and Tor Browser are some of the private browsers that block third-party trackers and scripts monitoring browsing across websites. This limits how much advertising networks can link visits from one site to another.

- DuckDuckGo, Startpage, and Brave Search are good search engines for privacy. They show results without building long-term profiles. Ads, when shown, depend only on the search terms entered at that moment.

- Proton Mail and Tuta Mail are secure email providers with end-to-end encryption, so only the sender and recipient can read them.

- Sync.com and Tresorit use zero-knowledge encryption for file storage, which means even the provider can’t access the content of stored files.

Alternatives to walled gardens

There are many tools and services that seek to empower internet users by decentralizing data ownership, reducing dependence on intermediaries, and promoting interoperability between services.

One direction is open protocols: technologies like ActivityPub, Matrix, and Bluesky’s AT Protocol. Open protocols enable social networks and communication platforms such as Mastodon to interact across different services. Users can move their profiles, followers, and posts between compatible platforms.

Another approach is the use of blockchain-based systems for identity, payments, and data storage. By distributing control across networks rather than central authorities, Web3 projects propose new ways to verify ownership and manage transactions directly between users. This can reduce reliance on the policies and infrastructure of a few large companies, though scalability and usability remain challenges.

A third path lies in privacy-preserving and federated technologies, such as decentralized search engines, open ad networks, and federated learning systems that train algorithms without centralizing data. These tools aim to maintain user privacy while still supporting personalization and monetization.

While none of these alternatives have yet reached the scale or convenience of large walled gardens, they represent early steps toward a more open and user-controlled digital ecosystem.

FAQ: Common questions about walled gardens

What does “walled garden” mean in the internet context?

A walled garden is a digital space controlled by one tech company. Everything inside it (apps, data, content, etc.) runs on that company’s systems instead of the open web. The company decides what can appear, which integrations are allowed, and what stays out.

Is Facebook a walled garden?

Yes. Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp all run within Meta’s closed network, where most interactions, ads, and data stay inside the same system. Links to external sites exist, but activity mainly happens within Meta’s platforms.

How does a walled garden affect advertisers?

Advertisers depend on each platform’s internal tools to reach users and track results. Data and reports stay within the platform, so results can’t be compared across systems. Access also comes with the company’s fees and policies.

Can I avoid using a walled garden?

While theoretically possible, this is difficult to achieve in practice because most major apps and services are closed systems. You can limit reliance by using open-source tools, privacy-focused browsers, or independent email and storage providers.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN